Between 1509 and 1511 A.D., Pope Julius II commissioned the artist Raphael to paint frescos in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, the building housing the papal living quarters. I’m no art historian, and I can’t tell you much about the first two frescos painted in the rooms now called Stanze di Raffaelo: La Disputa and Parnassus. But I have plenty to say about the third, Causarum Cogito, better known today as Scuola di Atene — The School of Athens. In my opinion, Rafael managed to capture about 90% of an undergraduate philosophy education in a single scene. I’ll explain.

But first, something fun happened this week. If you’re new here, welcome! If you’ve been here a while, you might not know that our subscriber base grew by about 150% since Monday after a shoutout from DJ Piehowski on the No Laying Up podcast. I can’t thank DJ and NLU enough for the bump. This newsletter actually started on the NLU message board, the Refuge, with an open letter to the NLU community following their NIT event. I assume everyone subscribed here also follows their stuff, but if not, stop reading this and go listen to their podcast on their favorite Masters.

If you’re new here and looking to flip through the catalog, here’s a brief overview:

“What Goes in the Bank” and last week’s “Slick’s Garage” have been my most successful pieces (by my own subjective measures). If you haven’t read these, definitely start here.

“Emotional Content”, from two weeks ago, was published 36 hours after my worst tournament start in a while, maybe ever. I hope it’s a good look at hitting a low and trying to make something of it.

“The St. Simons Open,” pts. one and two, are a more technical breakdown of how I approach an event, mid-tournament adjustments, and postgame assessments. If you’d like some nuts-and-bolts, pure-golf-sicko type content, go there.

Lastly, like maxing out ball speed on a par-5 tee after a sloppy bogey, I swung as hard as I could a few weeks ago and wrote “Temples.” It’s weird and surrealist, and it’s up to you if I found the fairway or not, but that’s as much clubhead speed as I have right now.

I mentioned that those first two pieces were my best by “subjective measures.” The goal of this newsletter is to deliver a meaningful, enjoyable part of your week that you’re glad to have show up in your inbox. In this sense, clicks-economy metrics (views, likes, etc.) succumb to Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. And so, to avoid becoming a cobra breeder[JB1] , I have an ask: if you enjoy something, dislike something, want to see more or less of something, or even have an idea for something totally new, please reach out. You can comment, DM me, or reply to these emails. To be clear, I have no monetary stake in any sort of engagement farming[1] — simply put, your feedback is the best way to help me make the most of your time each week by delivering the best possible product. If you have something to say, I’d love to hear it.

In any event, thank you for being here! And, a heads-up for this week: it’s about golf in the end, I promise.

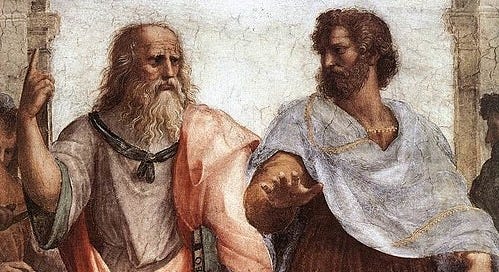

Rafael’s famous fresco, The School of Athens, depicts Ancient Greece’s thirty-or-so most relevant thinkers; Socrates, Euclid, Heraclitus, Epictetus, Pythagoras, Epicurus, Hypatia, Ptolemy, Zeno. But it saves its most famous subjects for the center, perhaps the two most influential western philosophers of history, standing in the midst of dialogue: Plato and Aristotle.

Courses are taught, dissertations are written, and careers are spent considering these two men’s texts. I was exposed to plenty of both when I was an undergrad, enough to appreciate how well this single painting captures a relevant summary of their thinking. Plato, older, balding, and barefoot, holds a finger pointed skyward. Aristotle, not just Plato’s contemporary but his student, stands a stride ahead with sandals and a lush beard, his hand outstretched, gesturing with his palm facing the ground.

As a physically-minded undergrad, it made sense to me that Aristotle would stand a step in front of Plato. Plato is best known for his Theory of Forms, that all things exist in relation to their ideal Form, that from which they get their nature — that all tables get their table-ness from the One True Table in the Sky. Aristotle wouldn’t accept this; without these tables here on Earth, there wouldn’t even be such a thing as this table-ness. Whereas Plato needed a higher realm to describe a thing’s true nature, Aristotle was practical enough to see that a thing’s properties arose from the thing itself. While Plato’s finger points up towards his daydream, Aristotle’s outstretched palm brings us back to reality.

But Aristotle is not The School of Athens’s central character — Plato occupies equal space in the fresco’s center. And, as I experience more life, the two maintain more of a dialogue. There’s what’s here, and there’s something else — after all, if there was only what’s already here, why do we imagine anything else, anything greater for ourselves? If there’s nothing but what’s here, when why, sometimes, does that feel so unsatisfying?

I did another round of contrast therapy this week, this time a new protocol. We set the sauna at 220°F and stayed in for 20 minutes this time instead of 15. Then, during the cold plunge (still at 33°), 30 quick deep breaths. On the 30th breath, I was to exhale all the way, force all the air out of my lungs, and then dunk myself fully underwater and hold the out-breath for 45 seconds.

Except, when my nose hit the water, I panicked. I’m not much of a breath-holder to begin with — I grew up asthmatic, and I’ve since relied on breathwork to steady myself in times of stress — and I barely got my hair wet before my spinal cord decided that my head would stay above water and that this was not up for negotiation. I tried to dunk myself again to no avail. We finished the protocol with a breath-hold above water, holding the out breath with my eyes fixed on the Tree of Life, the tall black cherry tree draped with Spanish moss in the neighbor’s yard.

Nystagmus had set in while I was still in the tub — the rapid shaking back-and-forth of the eyes as the vestibular system joins the fight to create body heat with muscle movements — but, back in the sauna, the shaking spread through my body until I was nearly convulsing on the wood bench. The panic escalating as I wondered why 220° wasn’t hot enough to warm me back up, it took a long round of slow, deep breaths to calm my nervous system down until the shaking stopped.

In meditation, to expect any specific result from practice — calm, insight, pleasure — is one of the more pernicious stumbling-blocks to real progress. The point of practice is simply to observe whatever’s there without expectation or preconception. Sitting on the bench, the panic lifting, I realized I’d come to this practice with expectations, wanting a continuation of the first round of contrast therapy, that euphoric peace, reminder that I’m one with all things, etc. etc. But real insight comes from observation without prejudice, and I settled myself to simply observe what was there.

I don’t think anyone chooses to be a professional athlete without a deep contempt for limitation. And this contempt yields one of the greater paradoxes of competitive life: that great performance comes from both striving for continual improvement and from the peace and confidence of accepting where one is. Sitting in the sauna, I realized I carry a deep resentment towards myself for my limitations. I’m good enough to play on Tour, but I’m missing mini tour cuts. I hit an absurd number of fairways at 190mph ball speed, but I’m still not hitting my wedges stiff. I should be able to hold my breath in a bathtub without panicking. I realized, as much as I value the practice of mindful observation without prejudice, I’m far from realization, from true acceptance — whatever’s holding me back from the guy I know I should be, I fucking hate it.

This is where my resentment extends to Aristotle’s outstretched hand. There has to be something greater than this, this limited self — something higher to aspire to, to pull down and become. I’m meant to be more than this. I have to be. Somehow.

It’s an interesting week for the subscriber base to explode, for two reasons in particular.

First, if last week’s entry (“Slick’s Garage”) was my first impression on you, you might know me as “that guy who boils his brain until he starts tripping on DMT.” I find this pretty funny given my prior experiences with drugs, which sum-total two halves of a legal low-caliber edible (to family members finding out about this for the first time, cheers!). On taking the first half, I went to a party, got massively self-conscious, and went home. Two weeks later, I took the second half with the plan to watch Fantastic Mr. Fox with a buddy. But he bailed on me (you know who you are and what you did), and I went to the library to write a paper until I got too stupid to write anymore, at which point I went to another friend’s place and questioned my self-worth on her couch for a couple hours. All of which makes it really, really funny to be seen as a big DMT guy.

As for the contrast therapy itself: I’m being extraordinarily safe. I’m a 24-year-old male in good shape, I’m acting on high-quality information from high-quality professional sources, and I’m doing it all under the direct supervision of a special forces medic (literally). My rant about pop-medicine and “doing your own research” is on the longer side, and I’ll relegate it to the footnotes[i], but, so I can sleep better at night: please do not take my enjoyment of these protocols as an endorsement that you should do them. Talk to a doctor before doing anything like this. Seriously. It's put me in some vulnerable spots that I needed guidance through. I’ve burnt part of my ears off. This stuff is no joke.

There’s a second reason it’s an interesting week to grow the tent: there’s a good chance your introduction here has been via one of my best pieces of writing. Writing this week’s newsletter has felt a bit like following up the 62 I shot in college. It’s hard to follow a great round with another great one, or even with a good one.

I went back through my two strongest newsletters looking for a way to recreate the magic, common threads to pull, a formula to follow. I found two things in common. First, they’re both in the bottom quartile of time spent writing and editing — they both came out in one draft and I hit send. And second, they’re interesting and fun because I had interesting, fun things happen to me. I met a pirate in a bar and bet a whole bunch of money on the golf course, and I boiled my brain and then changed my oil in a Tour winner’s garage. The formula for an exceptional newsletter is, more or less, to have an exceptional experience. I’m not sure if it’s realistic to expect that to happen each week — and I’m not sure what that means for newsletter quality.

I’ve had a tenuous relationship with the question “how?” I used to ask it as often as I could — it’s a question we overthinkers love asking. We want to do things well, and we’re smart people who like methods, and we want to do things the right way.

If you think about it, though, the question “how?” reflects one’s lack of faith in oneself. It defers to some rational third party, some “correct” way of doing things. It asks for a formula to execute — that way, if it goes well, we know what yielded the results; if it goes poorly, we can say we at least did it the right way.

But, if we really trusted ourselves, we wouldn’t have to ask “how?”. We’d simply trust our own capacity to do the thing we want to do. To ask “how” is to doubt our own abilities. And, for every person asking for a formula, there’s someone who trusts themselves and goes ahead and does the damn thing. They know they have all they need. And I doubt anyone’s natural talent, trusted and unleashed, has ever lost to a formula jotted down on paper.

I wonder if this means Aristotle has pulled ahead once again. Yes, thinking about Forms and formulas is seductive, imagining there’s some greater version of ourselves to pull down and inhabit. But really it’s just a distraction from the fact that we’re both all we have and all we need.

It might be this simple. But, if it was also this easy, we’d all have reached our full potential already. There’s still something to overcome in the question itself, something to learn to trust completely — and, in trying to build this trust, I find myself asking, “how?”

If it hasn’t been clear to this point: this is, in fact, a golf newsletter. But, truth be told, the golf from this week was pretty boring, bland, and uninsightful. I’m working on the same swing stuff I’ve been working on for a while, I tweaked my putter grip, and I’m still searching for a feel that can get me through a round. I’m still not scoring well, and I’m still not playing well. Even while the parts are improving, something’s yet to click.

Michael Thompson and my coach showed up at Paresh’s house to do contrast therapy after me, and we all had breakfast afterwards. Michael’s got the most impressive golf head on his shoulders I’ve ever gotten to talk to — he carries an impossibly simple and complete confidence. And he preaches this: make the game as simple as possible, execute with confidence and maturity, and know the difference between being correct and being effective (and choose the latter).

When I’m not playing up to my expectations, it’s easy to think the formula isn’t sophisticated enough. This time, it was Michael giving me the reminder that this isn’t true: that the way is simple. To be clear, Michael is a smart dude — it takes great intelligence to simplify a complex game into something excecutable and complete. Though, when he talks, I think the reality is even simpler than he says: that he just trusts himself, and that’s that.

If pressed, I’d tell you that Plato and Aristotle share that space at the center of The School of Athens as equals. Plato’s most famous work, Republic, details how various parts of the soul work together in unity. Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics does the same, describing how the rational soul habituates our emotional nature. Both describe the highest human good, virtue, eudaemonia, as bringing the various parts — intellect, emotion, imagination — together to work in harmony. I think it’s the same considering both philosophers: that we imagine something greater for ourselves, and we bring it down into reality only to realize it’s been here all along.

[1] I actually haven’t monetized this newsletter at all, yet. That said, I might monetize soon if I can swing it. If this feels like a good space to sneak a banner ad for your business, please reach out — I’d love some beer money.

[i] If you’re here for the science rant, then welcome!

First, a general disclaimer: I am not a health professional, and I am not giving any sort of medical advice. I hope it’s clear that my own personal enjoyment of contrast therapy is not a recommendation for anyone else to be doing it. I don’t know the medical research well enough to know even what to disclaim, which should be proof not to take my advice. My own consultations with trusted sources has led me to believe this is a good, safe thing for me, personally, to be doing. Please, be at least as rigorous (ie. talk to a doctor) before deciding to start anything for yourself.

My broader point: I lament that the idea of “doing your own research” has come to include reading websites that are 65% ads that try to sell you a pill/oil/device/book/course at the end. At some point, the line between thorough and precise discussions of rigorous, peer-reviewed scientific literature (see: Huberman) and talk about interesting theories (see: Rogan et. al.) got blurred — to the point that even labeling those two podcasters in such black-and-white terms is probably a little unfair (though I don’t think by much).

There’s a lot of economic incentive to promote poor science: either to sell ads on entertainment products or to sell pills/oils/devices/books/courses. The ground is especially fertile in new fields with limited research: 1) they’re new and buzzy and will drive viewership/consumers, and 2) they have less established research in the field, meaning bad actors can get away with bigger claims. As such, these cutting-edge fields are the places where you’re most likely to be sold snake oil — or something more dangerous.

When looking for quality information, I try to find quality, expert sources. Most of the time, this is on the NIH pubmed site, where you can read legitimate research papers. They’re technical and sometimes difficult to parse, but going straight to the source means you’re getting good information. If I’m not doing the research myself, I listen to people who I absolutely trust are qualified to speak on behalf of experts (usually, this means a professional I’m talking to has talked to a professional doing the research — that I’m only two steps removed from the primary source). I have greater access to these resources than many, but I really believe it’s the only way to ensure you’re getting quality information.

There’s two caveats here. 1) There’s no reason to look down on quality information given it’s adhered to the standards of rigor, replicability, and review that make science work. Science is egalitarian, and you don’t need to be a Harvard researcher to do great scientific work. Scientific information should be vetted based on the quality of the research, not the brand name it comes from. And 2) you’re the only you. Rigorous scientific studies look for gross impacts across large populations; if something has an effect in 10% of a sample population, the study won’t suggest a correlation. But the effect occurred in 10% of people, and you might be in that 10%. This gets risky, and saying “I’m in the 10%” does not exempt you from acting safely and protecting yourself from harm. But, if something truly works for you in your own N=1 study and you (and a doctor) are sure it isn’t doing you any harm, then it very well might just work for you. The world is complicated, and we find out more every day.

Good research is difficult, technical, and usually makes modest claims that are totally justified by the data. There’s a lot of incentive to make irresponsible claims that either aren’t backed by good research or draw conclusions that are too great for the data used. Unfortunately, these irresponsible claims are more entertaining, do better in social media posts, draw more podcast listeners, etc. And so people make a bunch of money and keep doing it.

These bad actors have given “doing your own research” a bad name, and the sketchier materials (see: social media, some podcasts, salesmen, etc.) has made it tougher to find the good science being done (see: peer-reviewed studies in reputable journals). But that stuff is out there, and the vast majority is accessible for free with an internet connection (the NIH pubmed site is an absolute wonder). Reading these studies doesn’t exempt you from talking to a doctor (!!!), but it can make you a more informed person with a better understanding of their own health and how to pursue it.

Alright. Rant over. Please: use quality sources!

I listened to your Substack piece “Formulas” on my walk yesterday. You are one brainy, multi-faceted genius! Had to Google “contrast therapy” to realize it is a variant of sauna principles and/or my Schule Schloss Salem 2x-a-day regimen . . . only more extreme. As always, your writing is a thing of joy, your knowledge of things vast and varied, your blunt honesty about golf, training & performance impressive, your tone oh-so-entertaining, and the effortless way you weave it all together superb. Thanks!

(Full disclosure: Connor Belcastro is my grandson)