Two weeks ago, I mentioned the reflexive property as a throwaway example in a larger discussion about the transitive property. Then, last week, I said I’d talk about the reflexive property. Then I put down 800 more words about the transitive property and didn’t mention the reflexive property at all. Today, I’m here to right those wrongs. By the end, you’ll also be able to read statements in first-order logic, so that’ll be fun.

First, a term to define: “numerical identity.” Numerical identity means that you’re talking about exactly the same thing. Similar objects don’t count. Neither do objects that look identical. Two ball bearings are not numerically identical to each other. Neither are two different hydrogen atoms. We mean precisely the same thing. If you point at two things, and you move your finger between pointing, then the two things are not numerically identical.

With that out of the way: the formula above is Leibniz’s Law, expressed in formal first-order logic. It only looks complicated because you don’t know what you’re looking at. Let’s run through what the symbols mean[1]:

So, let’s translate that formula into English:

In a single sentence: If X and Y are numerically identical, then they have all the same properties.

Congrats, you now have two fun new skills. 1) You can read statements in first-order logic. With some effort, you could probably pass a college-level intro logic exam (I’m, like, barely kidding). And 2), you’re equipped with a robust philosophical tool that you can use to be the most annoying person alive.

This might seem pretty obvious. Obviously my mug can’t be both red and black at the same time. My desk can’t be made entirely of wood and entirely of metal. I can’t be both 24 and 44 years old. Pretty straightforward stuff, until it isn’t.

Leibniz’s Law is especially fun[2] to use for contrapositives. These, technically speaking, are logically equivalent statements that you get by reversing the pieces of an if/then statement and making them both negative. For instance, if we started with “If it was raining, then the ground would be wet,” then we could say “The ground is not wet, so it is not raining.” Importantly: this sort of evidence is permissible in philosophical court.[3]

Maybe you’ve already guessed, but the real weight we can throw behind Leibniz Law is by contrapositives. If you can claim that something has two different properties, then you can (I swear) claim that the thing is not the same as itself.

Let’s consider two cases. First, two ball bearings. They’re the same size and the same shape, made of the same material in exactly the same way. You could swap them between any two machines and they would behave exactly the same.

Second, consider me, Connor. A few hours ago, I ate four eggs. When I woke up this morning, I had an empty stomach. Now, not only is my stomach fuller,[4] but I’ve started digesting those eggs. The sugars are in my bloodstream, the proteins are being broken down and rebuilt into my muscle fibers. A little bit of me is now made of the eggs I ate this morning.

Here's an argument you could make. Those two ball bearings are not numerically identical. I mean, there’s two of them. More technically, they have different properties of location — they’re in two different places. But their internal structures perfectly match each other. I, on the other hand, are about a quarter-of-a-percent egg-ier than I was this morning. I’m also sitting at my desk instead of laying in bed.

So, while both of us are in different places — the two ball bearings and me at two different times — I have more differences in my properties than the ball bearings. Which leads us to this:

The two versions of me are more dissimilar than the two ball bearings.

The ball bearings are not numerically identical.

Therefore, I am not numerically identical to myself this morning.

To be clear, this isn’t just to suggest that there’s been a change of some kind: Leibniz would have you believe that I’m genuinely not the same person that I was before. In this sense, every time I eat some eggs, a totally new thing comes into the world, and the egg-less version of Connor leaves it. In a very real sense, I’m not the same person that I was this morning.

There’s really two ways of dealing with stuff like this, as far as I can see. First, you can let it torment you, get a PhD in Philosophy, and spend a career (it’ll take a whole career) building a coherent system by which to track essential personal identity through time (“because I’m the same person, dammit!”). Along the way, you’ll learn about Locke’s memory theory, Parfit’s R-relatedness framework, and David Lewis’s theory of persons as four-dimensional mereological sums. You’ll also learn how these systems have weird corner cases that suggest that larger people are more socially valuable or that we should devote all our civilization’s resources to Armenian women. You can come up with your own theory of essential personhood, and you too can watch your theory be debunked by a grad student the year after you retire.

Or, if that’s not your speed, you can let these questions contribute to your sense of wonder, decide that this world is stranger than you could ever imagine, and then just live the rest of your life.

Q School is in five days. As a programming note: next week’s newsletter might be sparse or delayed as I try to get around Europe and one of those two most important weeks of the year. I also might have a ton for you. Who knows.

My favorite work I’ve done for this newsletter has been the more technical, professional stuff: going a few different directions, getting the pieces right, and putting it all together at the end. I’ve been looking for an angle to pursue from a golf side of things. Honestly, it’s all happening pretty quicky, and so I’m going in a direction a French film student might call “raw” or “real.”

I’ve felt pretty damn good about the state of my game for a while. After Australasia Q School, I figured that a bad week driving the golf ball was enough cause to make it my sworn mission to get my hand path on plane once and for all. It’s improved drastically. Then, a couple days after getting home, my driver cracked. Meaning it was probably on its last legs at Australasia.

I hadn’t had a bad week driving the golf ball in years, in terms of genuinely losing it both ways. And it seems reasonable to think, given that it cracked a couple days after the event, that the structural integrity of the driver was more likely to blame than my actual ability driving the golf ball.

Just how likely? Good thing I took that class on Bayesian statistics in college:

Where:

H: The driver was the problem.

¬H: Something other than the driver was the problem. (¬ = not)

E: The driver broke a week after the event.

If we assume H and H are 50/50, and that a driver is more likely to crack once it’s weakened, then the odds fall in favor of H, the driver being the reason for a poor week driving the ball. Given that I think these estimates are both conservative, the truth is probably vastly more so: that I can be reasonably certain the driver was to blame.

This kind of thinking is two things: highly logical and highly nuts. Sure, this sort of rigor makes me confident in the results. It gives me board-certified gold-plated permission to believe that the driver was more at fault than I was, and that a new driver will fix the problem. I have a new driver now. I should be in the clear.

But it’s all a bit like hunting with anti-personnel mines. Sure, you’ll probably get the deer. But it sure seems like the wrong tool for the job, which might say something about your skill as a hunter, and you probably won’t be left with anything useful at the end.

About those two ways of interpreting formal philosophy[5]. I really believe the highest function of the discipline is to make our lives better, full stop. So, in those cases when a tight snappy argument proves itself useful, then it’s doing its job. In those when it causes any consternation, annoyance, or dread[6], then the proper response is, basically, to say “huh” and not worry about it too much.

I got a four-year degree in the discipline. My senior spring, by which time I’d already finished my degree requirements, I took two more philosophy classes. I’m now using my newsletter to teach you about first order logic. I think I’d be lying to us both if I claimed I was good at saying “huh” and moving on. At the very least, it’s something to aspire to.

Back in February, before that GPro I wrote two letters breaking down, I was “so nervous I couldn’t even spit,” so they say. The night before the first round, I sat down with a copy of The War of Art and a legal pad. A couple hours later, I’d read the book cover to cover and filled two pages of the legal pad. That week is probably the best I’ve felt on a golf course as a professional, personally. Maybe that’s weird to say about a missed cut[7]; the word that comes to mind is a comforting sense of “clarity.”

Two takeaways here. First, another argument:

If I read The War of Art before I play a golf tournament, then I feel better.

I want to feel better this week.

Therefore, I should read The War of Art before this golf tournament.

Pretty simple shit that makes you wonder why, after such a great result, I haven’t read the thing before a tournament since.

I think the greater implication, however, has to do with the contents of the book — what the book does for me. You’d think that this sort of clarity, for an analytically minded guy who writes newsletters about Leibniz’s Law, that it puts some logical blocks together to formally clear up life’s big mysteries. Not the case. It’s just a really good book at convincing you do to your job and leave the rest up to fate, and that you’ll perform better the more you let go.

I have a pet theory that every conscious thought brings us a step further from the reality of the thing. And it’s ironic that, for someone seeking confidence — a basis for belief that I’ll do well — that I’ve found far more of it by such an irrational means as faith than by any form of reason.

Come Tuesday, I’ll be playing golf for status — Golf That Matters. This all comes on the heels of a year’s worth of missed cuts, and it leaves me desperately wanting some reason that this week is going to be different. I’ve wanted that for a lot of weeks. Each of these MCs, I’ve desperately wanted to believe that this week was going to be different, and then it wasn’t different. By that standard, it appears that I should stop believing that things will be different.[8]

But that’s not very useful. And, in the spirit of usefulness, Leibniz’s Law can help dig us out of this bind. If mere egg-eating is enough to make me a different person, then surely I don’t have to worry about being the same guy who missed those cuts. I’m a new man. There’s no need to be scared of things staying the same when everything’s always changing anyways.

I keep coming back to a Buddhist saying I heard from Joseph Goldstein: “The only thing we truly possess are the consequences of our own actions.” That includes any permanent, unchanging “self.” In a vastly simplified sense, our “self,” in any fleeting moment, is nothing more than the circumstances that led us there.

I’ve been waking up early and getting in two hours of putting before breakfast. And I’m putting a lot better. I acted, and the consequence is that I’m a better putter. I got an uncracked driver. I’ve made big steps to straighten out my hand path. I’m executing on golf shots better than I have in some time.

I’ve also been worrying. And, as much as I’ve done to get myself ready for this event, the worrying counts too. No matter how much time you put into practice, if you bring a worried, unconfident self to the first tee, you can negate all that practice pretty quickly.

But, when you start thinking about what’s causing the worry, it starts to make less and less sense. Worry that things won’t change is demonstrably stupid, because of course they’ll change. Then I’m just worried that they won’t change in the right ways. In which case, I’ve been putting the work in. So, if I possess the consequences of my actions, then, quite literally, the only thing I’m bringing to this tournament is my preparation.

In which case, the only thing that could sink me is the very act of worrying. A statement, that, as a worried person, makes me worry — expressed improperly, and it sounds like I’m doomed to all this worrying I’m doing. But that would mean that nobody who’s won a golf tournament has questioned themselves beforehand, and that’s clearly pretty silly to suggest.

At this point, I’ve been letting the over-thinker in me run wild for 2800 words. Part of this is because I’m really quite nervous and really have a tough time not-thinking. Mostly, I’ve let myself follow the thread because it makes for good material.

But it’s time to take my own advice and rise above all that. Puzzles are interesting and all, and it’s fun to see what kind of logical corners we can back ourselves into. And to consider what happens when I get eggier. But the reason we can think about all this without letting these logical binds ruin our lives is because, deep down, we all know the truth to be far simpler.

Before the Masters, Rory McIlroy talked about “chasing the feeling,” a state of mind in which he knows he can win. The Buddhists are pretty clear about trying to “create” feelings — what’s there is already there, and all you can do is observe it. Rory did, indeed, win the Masters, successfully chasing that feeling. At which point, if we’re insistent on being formally logical, the takeaway is pretty simple:

If you can chase a feeling, it was already there.

You can chase a feeling.

So, the feeling is already there.

Everything I need is already with me. Although, of course — given I know it works — another read through the War of Art surely can’t hurt.

With that, onwards to Belgium.

[1] A disclaimer here: I’ve started using Claude. I’ve been using it to build shitty financial models in python and condense the zillion things I want to do every day into an actionable plan. It’s also great at refreshing my memory on the technicalities of first-order logic, and things like “make a table explaining what these symbols mean” (which I then edited because I didn’t like it).

I feel like this is the kind of thing a writer should disclose, for some reason. Rest assured: I’m still the one writing. How can you tell? Because I had Claude write a newsletter, and it totally sucked. So it seems like we’ve still got the robots beat in terms of, you know, having human experiences and such.

You can be damn sure you’re not just reading a bunch of AI generated text, but in the spirit of full transparency, yeah, Claude is pretty good at some stuff.

[2] Fun in the same way that lighting off fireworks in your garage is fun — exciting, but the kind where your nervous you’re going to burn your house down.

[3] Every time I use the word “philosophy” or “philosophical” as a big monolith to say “hey, I’m the philosophy guy,” I cringe so hard that three hairs fall out of my head. Comment an alternative before I go completely bald.

[4] Not entirely — I’m starting to get hungry again.

[5] Another dollar in the swear jar — a few more of these and I’m gonna get a nosebleed.

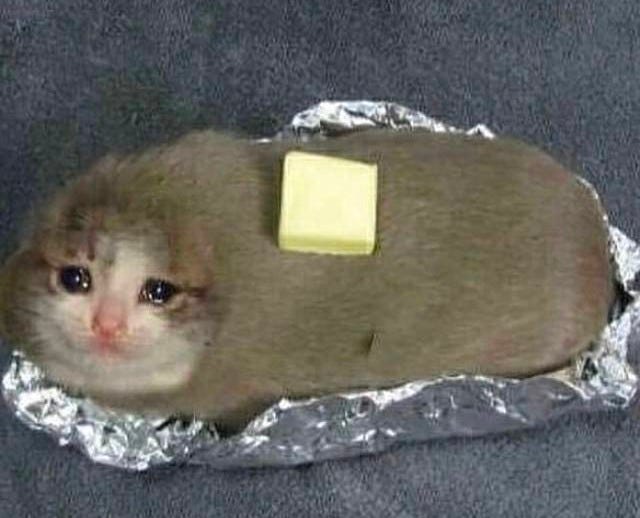

[6] Anything of this flavor

:

[7] Actually, it’s a logical necessity — the best I’ve felt was an MC because they’ve all been MCs!

[8] ∀x( R(x) → B(x) ), where R is a reason and B is bad.